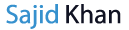

Appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in the United States. Nearly 9% of all men and 7% of all women will be afflicted at some point in their life. Despite this ubiquity, there are countless pitfalls one can encounter before reaching the diagnosis and in subsequent management. Here is an article published by myself and the brilliant Dr. Arshad from this month’s issue of Emergency Physicians’ Monthly on ten tips to not missing this critical diagnosis:

1. Anytime, anywhere, any place

The classic presentation of acute appendicitis is a migratory abdominal pain that begins in the peri-umbilical area and spreads to the right lower quadrant, associated with anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Unfortunately, diseases don’t follow proclivities, patients don’t attend medical lectures and an appendix is incapable of reading journal articles. Most patients present in the first 24 hours, and the risk of rupture rises dramatically after the first 48 hours. However, ‘chronic appendicitis’ refers to inflammation that may cause pain lasting for weeks, months, or even years. Moreover, there are case reports of patients who have presented with left-sided pain, and in this author’s experience, atypical presentations of pain are so common they are no longer worth reporting.

In pregnancy, the pain may be located in the right upper quadrant as the growing uterus causes displacement. An inflamed appendix may cause pain in the epigastrium, hypogastrium, right side, left side, suprapubic area or even the back. Put simply: the classic triad of right-sided abdominal pain, anorexia, and nausea is not so classic. The mere presence of abdominal pain in any patient warrants the addition of appendicitis to a differential diagnosis. Right-sided abdominal pain should be considered appendicitis until proven otherwise.

2. White blood cell counts are the best and the worst

White blood cell counts are terrible. They can be high or low. Shifted left or right down the middle. In the entirety of medicine, a white blood cell count cannot be used to rule in or rule out any single condition. Still, approximately 80 percent of patients with appendicitis will have leukocytosis. If the white blood cell is raised and there is clinical suspicion for appendicitis, you must act on this information: be it through imaging studies, surgical consultation or admission for serial examinations. Ignore an elevated white blood cell count at your own peril. If your initial clinical suspicion is low and the white blood cell count is normal and you wish to avoid imaging for some reason (for instance: cost, radiation, length of stay, patient preference, etc), discuss your concerns with the patient and allow them to make a decision. Document.

3. C-reactive proteins are simply the worst

C-reactive proteins are non-specific inflammatory markers. They have been well-studied with regard to the diagnosis of appendicitis and many studies have demonstrated a significant predictive value when combining this test with an elevated white blood cell count. An isolated elevated CRP means little; in the presence of leukocytosis, one should not need a CRP level to consider the diagnosis of appendicitis. This study is a send-out test at many community hospitals, meaning it may take greater than 24 hours to results. C-reactive proteins are a perfect example of the difference between ‘textbook medicine’ and clinical practice.

4. Don’t let the urine fool you

Urinalysis should be ordered in [nearly] all patients with abdominal pain as it is useful for determining pregnancy status, evaluation for infection, and identifying hematuria. However, attributing pain solely to a urinary tract infection should be done with caution. An inflamed appendix can abut the ureter and cause ureteral inflammation, resulting in white blood cells being present in the urine. The presence of white blood cells without bacteria should raise suspicion for something other than a urinary tract infection. Remember: there is no single sign, symptom, or lab that rules out appendicitis. Occam’s razor is a guiding principle that, simply stated, implies the most likely explanation is often the correct one. Hickam’s dictum is a counter-argument, which can be paraphrased as: patients can have as many diseases as they darn well please. Choosing to follow Occam’s razor will put you on the fast track to bouncebacks, patient complaints and frequent visits to the peer review committee.

5. CT is the gold standard, but there are exceptions

Aside from direct visualization through surgical intervention, a computed tomography (CT) scan is the most sensitive and specific test available for diagnosis of appendicitis. There are instances in which an ultrasound can be considered first-line imaging however: most notably in children and pregnant women.

For pregnant women in whom the ultrasound is inconclusive, an MRI is the next preferred test as it avoids the ionizing radiation of a CT scan. Compared to ultrasound, an MRI is more likely to show the peri-appendiceal findings when the appendix is not visualized. Ultrasound may be performed at the bedside and also provides the benefit of minimizing ionizing radiation exposure as compared to a CT scan. Of note, an appendix that has perforated makes ultrasound less accurate.

6. Use clinical decision tools with care

There are three widely discussed clinical decision tools with regards to appendicitis. One has been identified as particularly helpful in the pediatric age group: the Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS). In a 2009 validation study, patients between the ages of 4 and 18 were enrolled that had abdominal pain for less than three days duration with clinical suspicion for appendicitis. Using criteria including anorexia, emesis, leukocytosis, and migration, among others, scores less than four helped rule out while scores greater than eight helped predict appendicitis. The Alvarado Score and Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score (AIRS) lack the appropriate sensitivity or specificity to be of any value alone. They have shown benefit in risk stratifying the need for imaging studies, however.

7. A negative workup means nothing

‘Stump appendicitis’ is a late complication of surgical treatment that is defined as an inflammation of any residual tissue of the vermiform appendix that remains after an appendectomy. One theory is that the use of laparoscopy has increased its incidence due to failure to invaginate the stump into the cecum during surgery.

‘Tip appendicitis’ is another condition that may be difficult to diagnose. If appendiceal obstruction and inflammation is limited to the distal portion of the appendix, the CT scan may be falsely negative. If your index of suspicion is high, even in the setting of a negative workup, surgical consultation and admission may be warranted. Every patient discharged home after a negative workup should receive appropriate return precautions.

8. Broaden your horizons

Perform a good physical exam. Male patients with abdominal pain deserve to have their testicles examined for torsion and other pathology. In females, consider gynecologic diseases including ectopic pregnancy, ovarian toarsion or tubo-ovarian abscess. Just as it is imperative to place appendicitis on the differential of most patients with abdominal pain, it is important to keep a broad differential diagnosis.

9. One letter makes a big difference

Here’s a scenario that will happen to nearly everyone at some point: you have a patient in whom you are strongly considering appendicitis. A CT scan is ordered and the radiologist writes ‘epiploic appendagitis’ in the impression. Epiploic appendices are small projections or fat-filled sacs along the upper and lower colon and rectum. They may become inflamed, leading to pain anywhere in the abdomen. There may be loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and an elevated white blood cell count. It differs from appendicitis in that it is a benign, non-surgical condition often treated with anti-inflammatory medications. Outpatient laparoscopy may later be performed to prevent recurrence.

10. Don’t put away the scalpel just yet

In a controlled study among 540 adults, 257 patients were randomized to antibiotics. Of these, 28 percent required subsequent surgery up to one year later. There is still no large randomized controlled trial in which patients with uncomplicated appendicitis are assigned to either antibiotic or surgical treatment and followed for a number of years. Antibiotics alone may be a reasonable option for non-perforated acute appendicitis, but a significant number of these patients may develop recurrent appendicitis within one year. In the meantime, initiating IV antibiotics directed against gram negative and anaerobic organisms and immediate surgical consultation for appendectomy remains the definitive treatment. Physicians will, appropriately so, be cautious to adopt a non-surgical approach given the litigious nature of this condition.

11. Protect yourself

Missed appendicitis is the leading source of malpractice suits against emergency medicine physicians in adult patients with abdominal pain. It is also the second leading source of malpractice suits against emergency physicians for children age 6 to 17 years of age. Maintaining appendicitis on your differential diagnosis, remaining diligent in your workup and close outpatient follow-up for negative workups provides the best protection.

Source:

http://epmonthly.com/article/dont-miss-the-most-common-abdominal-emergency/