Here’s an excerpt from How to Not Kill Your Patients, a collection of interesting stories, cases, and advice for those who work in the ER:

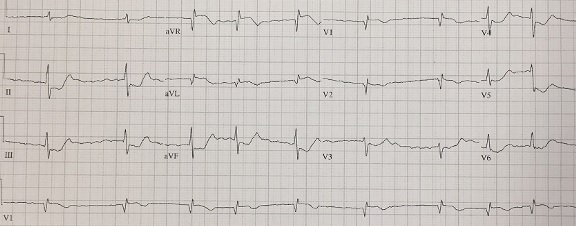

A 70 year-old woman presents to the ER with mid-sternal chest pain, shortness of breath, and diaphoresis. She’s clutching her chest with her fist a la Levine’s sign. A textbook presentation. Here is her initial ECG:

There is isolated ST elevation in aVR and inferolateral ST depression. That’s a STEMI! Or is it?

This is what the 2013 ACC/AHA STEMI guidelines say about it: “multi-lead ST depression with coexistent ST elevation in lead aVR has been described in patients with left main or proximal left anterior descending artery occlusion”. Activate the cath lab!

The cardiologist came down to see the patient, canceled the cath lab activation, and elected to treat her with medical management. She underwent a catheterization the next day and was found to have a 98% RCA lesion and 40% LAD stenosis.

For years, aVR was the forgotten lead. More recently, it has started gaining notoriety as a way to identify otherwise potentially missed left main coronary artery (LMCA) occlusions. At this point, we should make a critical distinction: there is a difference between an ‘occlusion’ and an ‘insufficiency’. When relying on evidence for the basis of the 2013 guidelines, the AHA cites a study in which ‘occlusion’ was defined as any stenosis greater than 50%. We know that this grade of stenosis is best managed medically and the true definition of an ‘occlusion’ should be at or near 100%. In fact, all of the articles that claim ST elevation in aVR as representative of LMCA occlusion use ‘occlusion’ as a substitute for ‘insufficiency’.

Only 0.19% – 1.3% of STEMI patients have LMCA occlusion, in part because most patients don’t survive long enough to make it to the cath lab. A true left main occlusion would rapidly lead to STEMI, cardiogenic shock, and death – and isolated aVR elevation simply does not portend such a diagnosis. Put another way: the need for cath lab activation due to a left main coronary artery occlusion is typically apparent from the clinical presentation.

A 2013 study published in the Journal of Electrocardiology collected 133 ECGs of patients with ST depression in seven or more leads and ST elevation in aVR. 26% of such patients had no significant coronary artery disease and left main disease was only found in 23% of such patients. The authors concluded that in patients with diffuse ST elevation and isolated aVR elevation, the term ‘suspect circumferential subendocardial ischemia’ was more accurate than ‘left main coronary artery disease’.

aVR does have some utility which cannot be questioned. Patients with recognized STEMI have a higher mortality rate when there is also elevation in aVR compared to those who do not. Additionally, in the setting of an acute coronary event, ST elevation in aVR is associated with multi-vessel disease.

Should widespread ST depression with ST elevation in aVR be considered a STEMI-equivalent? The problem is that such depression is just as common in non-coronary causes of ischemia (GI bleed, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, etc). If acute coronary syndrome remains at the top of your differential, it is reasonable to initially treat such patients with medical management (Aspirin, Nitroglycerine, etc). The chest pain and ECG findings may resolve. If symptoms resolve and the ST depression rescinds, the patient can wait to go to the cath lab.

So how to best handle this? Since there is still some substance to this debate, it’s best to err on the side of caution. If a cardiologist is not readily available, I would recommend activating the cath lab to get them involved early. A prompt conversation and review of the ECG may lead the cardiologist to cancel the activation, but it’s best to make that decision together.

In the timeless words of Dr. Stephen Smith, one must evaluate the patient, with help from the ECG.

Learning points:

1) ST elevation in lead aVR is neither sensitive nor specific for an acute LMCA lesion

2) Look at the patient first and then correlate your clinical suspicion with the ECG

3) Lead aVR is not a savior but it should not be ignored

4) Engage in shared decision-making with the cardiologist

Find more topics like this in How to Not Kill Your Patients!