The Importance of Good Return Precautions

The setup

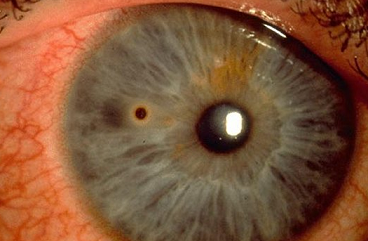

An elderly man slips on an icy spot in his driveway and falls back, striking his head against the concrete. He takes warfarin, and in the ED a CT scan of his head is read as normal. He is discharged home only to return two days later with ‘altered mental status’. The family reports that his level of consciousness has progressively declined since the fall. On the second visit, labs reveal an INR of 2.6, and a repeat CT is as follows:

The official interpretation is: “anterior left temporal intra-axial acute hematoma, very small overlying acute extra-axial hematoma”

The conundrum

You’re in a rural hospital with no neurosurgical coverage. What should you do next?

A. Admit the patient to your hospital for serial neuro checks and transfer if the patient begins to decline

B. Transfer the patient to the nearest facility with a neurosurgeon and intubate in case he decompensates en route

C. Order vitamin K 10mg subcutaneous injection

D. Order fosphenytoin 1000mg for seizure prophyalxis

E. Order Kcentra

F. Put the chart back in the rack and pretend you never saw it

Discussion

There is a lot to learn from this case, so let’s not waste any time.

This patient was given excellent return precautions on his first visit. There is a plethora of information arguing both for and against admission for all anticoagulated head injury patients.

The current European guidelines suggest a period of observation in the hospital and repeat imaging. Studies have shown a delayed ICH rate of 0.6% to 6% for warfarin. But how many of these were ‘clinically significant’ bleeds?

Another study found the bleed could occur anywhere from days 2-28. Should these patients be tying up an inpatient bed for one month?

Overall, accepted practice is that if the initial head CT is normal and the patient’s examination is normal, consider discharge with close follow-up if the patient/family seem reliable.

Working in a rural area presents its own set of challenges. Lack of access to specialists can be a real challenge and a big adjustment for someone used to working in an academic setting. No one wants to be woken up, curbside consulted, texted, or bothered with your patient unless there is some acute emergency that they need to know about right now. Like this head bleed. This is not the kind of thing you admit and watch. This patient needs to be transferred immediately, but there are some things to do before loading them up in an ambulance.

Reversing coagulopathy is key. To this end, vitamin K is a great agent to use for reversing warfarin’s effects. When choosing how to administer vitamin K, there are three options: oral, subcutaneous, or IV. Of these, the subcutaneous route is generally frowned upon as there is erratic absorption and unpredictable clinical effect. The oral route is preferred in awake patients who can easily swallow pills and in whom reversal of coagulopathy is not super-emergent; in our case the patient received 10mg IV. Choosing the dose (1mg vs 5mg vs 10mg) is an imprecise science but if you’re quickly trying to prevent a brain bleed from expanding it’s better to overshoot than to underdose.

What about anaphylaxis?

When given by the IV route, vitamin K can cause an anaphylactoid reaction. The rate of this reaction is comparable to IV contrast that’s used during CT scans.

Kcentra is PCC (prothrombin complex concentrate) and is made up of clotting factors II, IX, and X. It’s given slowly through an IV and the only real contraindications are DIC or a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. It corrects coagulopathy much faster than vitamin K but is best used in combination with it. Our patient received PCC in addition to vitamin K.

Summary

Anticoagulated patients who fall or have trauma deserve your utmost attention. Even if there is no concern for injury at the time of their initial assessment, good return precautions are essential.

References

- Cohn B, Keim SM, Sanders AB. Can anticoagulated patients be discharged home safely from the emergency department after minor head injury? J Emerg Med. 2014 Mar;46(3):410-7.

- Miller J, Lieberman L, Nahab B, Hurst G, Gardner-Gray J, Lewandowski A, Natsui S, Watras J. Delayed intracranial hemorrhage in the anticoagulated patient: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Aug;79(2):310-3.

- Schoonman GG, Bakker DP, Jellema K. Low risk of late intracranial complications in mild traumatic brain injury patients using oral anticoagulation after an initial normal brain computed tomography scan: education instead of hospitalization. Eur J Neurol. 2014 Jul;21(7):1021-5.