Prescription drug overdose has surpassed motor vehicle accidents as the number one cause of unintentional injury-related death. For the suspected opiate overdose who is unresponsive, there are few options outside of endotracheal intubation and supportive care. Naloxone (Narcan) is generally regarded as safe and with minimal adverse effects. It can be administered via an IV, IO, IM, SQ, or inhalational route. Its onset is within two minutes and duration of action is 20-90 minutes.

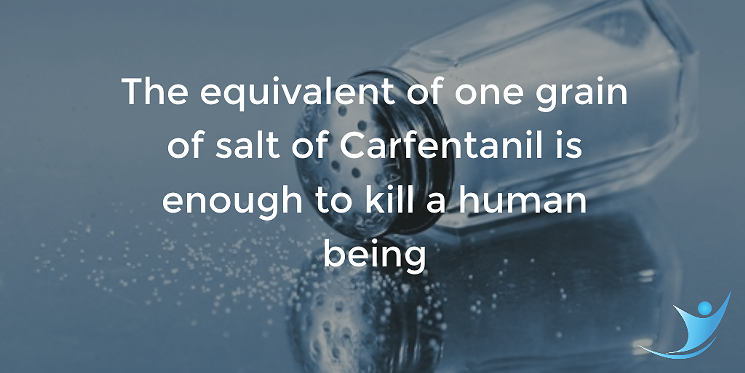

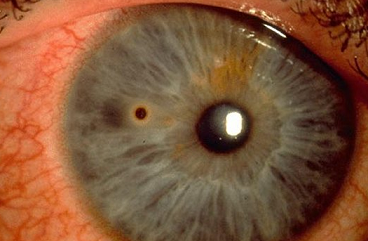

Reversal of respiratory depression — not CNS depression — should be the goal when administering Narcan. The greatest risk with Narcan use is ‘opioid withdrawal syndrome’ (OWS). Rapid reversal may cause vomiting, agitation, seizures, hypertensive emergency, or pulmonary edema. In patients treated for severe pain with an opioid, high-dose Naloxone and/or rapidly infused Naloxone may cause catecholamine release and subsequent pulmonary edema. For this reason, it is typically administered in 0.4-2mg doses when given IV. There are exceptions to this, most notably Carfentanil – actually an elephant tranquilizer that started gaining notoriety in 2016. It is 10,000 times more potent than morphine and requires significantly higher doses of Narcan. Initial doses typically start at 10mg IV.

Once Narcan has been administered and patients have responded, in general, they should be advised to stay for at least four hours of monitoring. There’s been an unfortunate trend of patients receiving pre-hospital Narcan and wanting to leave immediately upon arrival to the ER. Numerous studies have been done to ascertain the ideal period of observation and the risk of recurrent respiratory depression but they are fraught with inherent inadequacies. As mentioned with Carfentanil, more potent opioids require a longer period of observation. For isolated heroin use, 1-4 hours of observation is probably enough. For methadone overdose, given its longer half-life, a longer period of observation would be necessary. A patient’s underlying tolerance and co-existing conditions will play a role in metabolism – all of these factors are difficult if not impossible to control when attempting to determine the ideal period of observation. It’s difficult to justify legally holding someone against their will – someone who is now alert, oriented, has a way to get home, and can reasonably listen to your recommendations and repeat them back to you. Be sure that after the Naloxone has worn off, there is no recurrent toxicity. Document, document, document.

Data suggests that if a patient refuses transport at the scene or wants to sign out AMA after receiving Narcan, there’s a low risk of death. A four hour period of observation is recommended but not always feasible. In my personal experience, I can typically talk patients into staying for one hour, which, at a minimum, is a safe period of observation.

One story that has gained notoriety in mainstream media is that of a police officer in Ohio. He made a routine traffic stop and noticed a white powder all over the perp’s vehicle. About one hour later, the officer was back at the station and someone mentioned that he had some powder on his shirt. Without thinking, he brushed it off. He immediately fell to the floor and several hours and doses of Narcan later he was released from the hospital. Here’s how his police chief described the risk:

“Think about this: Nobody sees that on his shirt. He leaves and goes home, takes off that shirt, throws it in the wash. His mom, his wife, his girlfriend goes in the laundry, touches the shirt — boom. They drop. He goes home to his kid. ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ They hug him — Boom. They drop. His dog sniffs his shirt, it kills his dog. This could never end.”