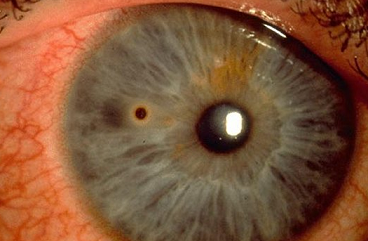

Don’t confuse the ‘knee’ for the ‘knee-cap’! There are a select few indications for getting an orthopedist to come to the ED in the middle of the night, but a true knee dislocation might be one of them. I remember being an ER resident on my orthopedic rotation and getting the call that there was a dislocated knee. I had to leave a fancy dinner to race to the ED but did so without any regret. I couldn’t wait! Would it need bedside reduction? Would the patient have an emergent angiogram? Would he kneed (see what I did there?) operative intervention? So many questions….only none of them kneeded (I’ll stop now) to be asked. The patient had a patellar dislocation that was already reduced and required nothing more than an immobilizer, crutches, and outpatient follow-up. If nothing else, this experience imprinted in my mind the importance of three letters: c-a-p.

One such patient presented recently with the following x-rays:

Now this is a true knee dislocation. The knee is held together primarily by four ligaments: the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL. Three out of four of these must be affected for the knee to dislocate.

Post-reduction films:

Treatment is to reduce, immobilize, and operate. Timing of surgery is a little murky but most experts agree that waiting 1-2 weeks is the most reasonable approach.

Should all patients have an emergent angiogram? The textbook answer is also unclear, with most sources recommending ‘selective’ angiogram, but it would be tough to argue against ordering an MRA or at least a CT-a for every knee dislocation. It’s a rare enough presentation as it is, that you would hate to miss that added complication.

Here’s a nice video on how to reduce.