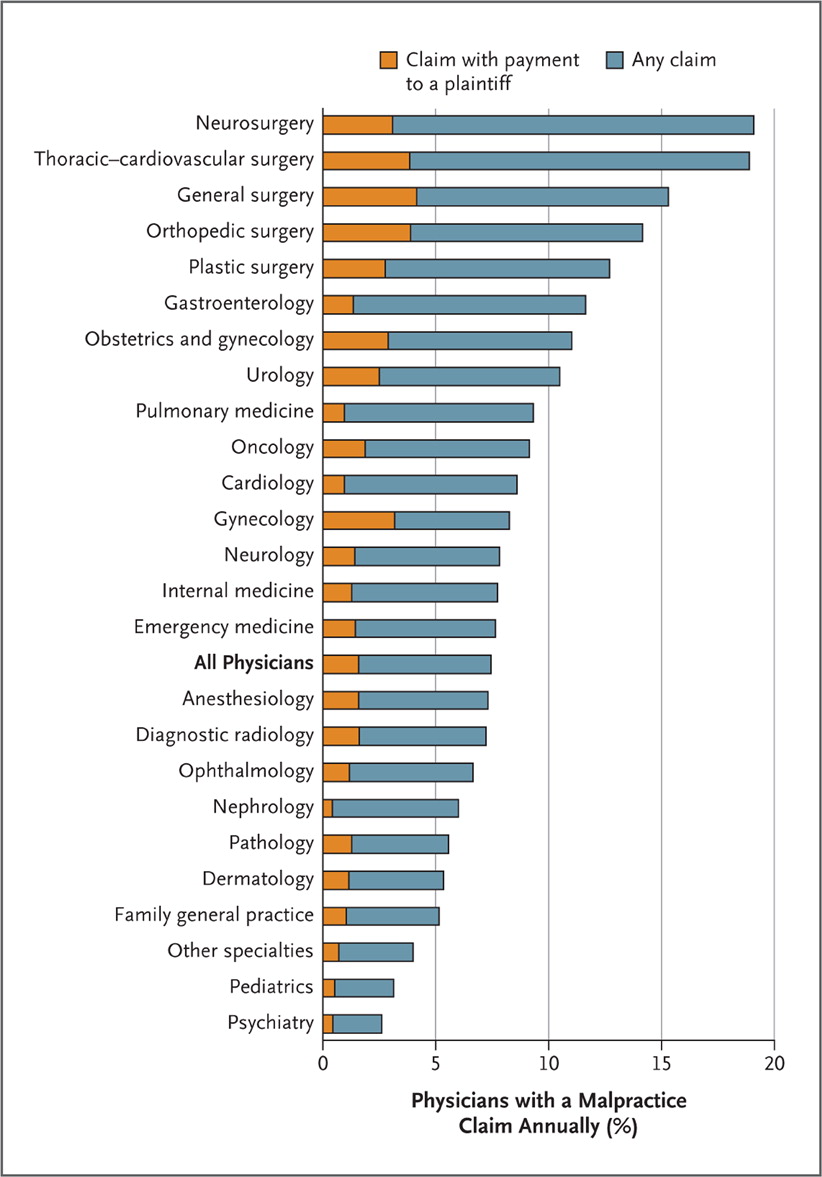

We work in a high-risk field. The very nature of emergency medicine and the types of patients it attracts is litigious. A 2011 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that EM had a higher than average risk of malpractice. It states: “The proportion of physicians facing a claim each year ranged from 19.1% in neurosurgery, 18.9% in thoracic–cardiovascular surgery, and 15.3% in general surgery to 5.2% in family medicine, 3.1% in pediatrics, and 2.6% in psychiatry.” In other words, nearly 1/5 neurosurgeons will have a malpractice compliant brought against them in one year. Here’s the graphic they published (source N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 18; 365(7): 629–636.)

I’m actually quite surprised that EM ranks as low as it does, and have to believe that exploding volumes and increasing reliance on metrics has only worsened the state of our malpractice risk. With that in mind, here is a real case with real numbers (all identifying information changed to protect patient privacy of course):

A 50 year old male presents with ‘sore throat’. He has a history of diabetes. Initial vitals are as follows:

BP 131/77, HR 78/m, RR 17/m, temp 36.1 C, O2 sat 98% RA

Let’s pause for a second and convert that temp to Fahrenheit: 96 F

He is seen by a nurse practitioner who orders labs; significant findings are:

Na 131, CO2 20, Creat 1.8, Gluc 456, serum acetone positive, urine ketones positive, urine glucose > 500

He’s given one liter of IV fluids and discharged home with a diagnosis of ‘pharyngitis’ and ‘dehydration’. Vital signs are not repeated. He returned less than 24 hours later in rigor mortis and pronounced dead.

The first chart was signed by an attending physician who never reviewed the labs or vital signs. It’s clear that the NP considered DKA as a possibility as a serum acetone test was ordered – yet somehow all of the abnormal findings were overlooked. The vital signs were overlooked. The case was never discussed with an attending while the patient was in the ED.

Don’t take unnecessary risks with your license. Control whatever chaos you can: that means read through your midlevel’s charts, even if it’s just skimming the vital signs and labs. As firmly as I believe in this, I still find myself overlooking charts written by midlevels that I trust and have built a solid working relationship with. But ignorance and a false sense of comfort is no excuse. Be diligent in this and it will only benefit you and your patients.